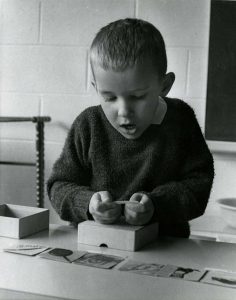

Maria Montessori (1870-1952), the first woman in Italy to receive a medical degree from the University of Rome, developed her theories of education at the turn of the century while working as a young doctor in an asylum for mentally disabled children. In the Montessori method, children use special learning materials in a prepared environment to sequentially develop and master concepts and motor skills. Teachers guide but do not control, each child progresses at his or her own pace, and the noncompetitive atmosphere of the classroom allows working for the pleasure of learning rather than from fear of punishment or anticipation of rewards.

Dr. Montessori developed an international following, and in 1913 and 1915 she toured the United States, lecturing on her educational theories to enthusiastic acclaim. Yet by the 1920s her ideas had been rejected by mainstream American educators. This effectively killed the Montessori movement in the United States for the next several decades, although it continued to flourish in Europe, especially among Catholic educational institutions.

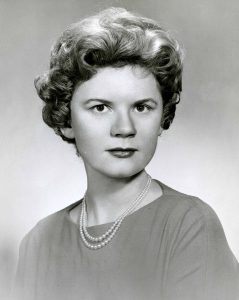

In the late 1950s Nancy McCormick Rambusch, a young teacher who had undergone Montessori training in London, became inspired with the idea of reviving Montessori education in America. Initially conducting classes from her New York apartment, she soon founded and became headmistress of Whitby, a lay-Catholic school in Greenwich, Connecticut, which became the flagship school of the American Montessori revival. Rambusch and Whitby gained a reputation and supporters; they and the Montessori method soon became the subjects of articles and interviews in both Catholic and secular journals and magazines. They also attracted the attention of the Association Montessori Internationale (AMI), the guardian and promulgator of Maria Montessori’s ideals under the directorship of her son, Mario, who authorized Rambusch to act as AMI’s representative in America. This led, in 1960, to the founding of the American Montessori Society (AMS), with Rambusch as its first president.

During the early years the fortunes of AMS and Whitby School were intertwined; the two institutions even shared Board members. These years have been described as a time of ceaseless activity, with AMS, Whitby activities, and teacher training running morning, noon, and night, seven days a week. The atmosphere in these early years has been described as both full of life and chaotic, as responsibilities to AMS and Whitby absorbed the full time and attention of Whitby teachers and members of the new society. As national demand for information about the Montessori method grew, Rambusch left Whitby to devote her attention to the promotion of AMS. For documents related to Nancy McCormick Rambusch’s departure from Whitby, see AMS, AMI, Whitby, January-May 1962 and the Jack Blessington Interview.

Nancy McCormick Rambusch was a leading proponent of modifying the Montessori method to fit American culture. While she believed that Montessori education in America should start with the classic model created by Maria Montessori, she sought greater flexibility in the materials used to teach students, the ages at which students were supposed to master certain skills, and the role of Catholicism in Montessori education. Although Rambusch was active in Catholic circles, she recognized that Montessori had to transcend religious boundaries and would have to acquire nonsectarian appeal if it was to succeed in the United States. She also firmly believed that aspects of the Montessori method had to be modified to accommodate the culture of mid-twentieth-century America and its children, and that the movement should not be confined to private institutions.

These ideas strained relations with AMI, which felt that Dr. Montessori’s principles were universal and could not be modified without destroying their integrity. Despite good-faith attempts on both sides, the philosophical differences could not be reconciled, while additional controversies over finances and control deepened the rift. Ultimately, in 1963, AMI withdrew its recognition of AMS as a Montessori society, and from that point until the present AMS has existed independently of AMI.

Within AMS, the administrative affairs of the office were in chaos, and the organization was in danger of disintegrating. This situation was remedied when Cleo Monson was hired in January 1963 as Executive Secretary to reorganize AMS’s office, but her administrative abilities soon rendered her indispensable as the coordinator of virtually all the society’s activities. In 1973 she became the first National Director, a position of pivotal importance that she essentially created and that she held until her retirement in 1978. In her own way she was as responsible as Nancy McCormick Rambusch for the existence of AMS.

In 1963, six months after Monson arrived, Rambusch resigned as president and embarked upon a distinguished career in children’s education that continued until her death in 1994. Also in 1963, the national office of AMS moved from Greenwich to New York City, where it has since remained.

Following the turbulence of these early years, AMS found firmer footing and began to flourish. As the society grew, it had to cope with the practical issues that face all organizations, including fundraising, formation of policies, codification of professional standards and ethics, and public relations, both within and without the Montessori community. Various committees and programs sprang into existence to meet these needs, and this required the talents and resources of members willing to organize and direct these important activities. Within a decade of its existence, therefore, AMS’s internal structure necessarily increased in complexity. Yet the society continued to avoid bureaucracy as much as possible by using the main office in New York as a coordinating hub.

Because Montessori schools were not required to affiliate with the national organization, AMS sought to establish relationships with local schools through various forms of outreach. It published literature about the Montessori method and AMS, collected research, some of which appeared in the society’s various journals and newsletters, and established the Consultation Program, in which trained consultants would visit affiliated schools, observe classes and the physical environment, and offer suggestions and feedback. AMS developed standards for teacher training and certification as well as pedagogical resources to meet Montessori educational needs.

AMS’s seminars and conferences also served to foster communication, professional growth, and a shared sense of identity among Montessori teachers. A national seminar was held annually, and several regional conferences took place each year. These meetings featured lectures, workshops, presentations, and exhibits, and allowed members to network, exchange ideas, and develop or hone their teaching skills. Portions of these seminars were recorded or filmed to serve as future resources. The society was very proud of the success of its first International Symposium, held in Athens in 1979, which featured as speakers several internationally renowned educators and scholars.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, AMS constantly sought to widen its appeal. Its ties with the Comite Hispano Montessori, for instance, enabled the Montessori method and resources to thrive in Spanish-speaking communities in the Americas and the Caribbean. AMS collected literature from and established relationships with other educational groups and organizations, including the National Association for the Education of Young Children and the Child Development Associate Consortium, and concerned itself with home schooling, day care, and alternative educational methods such as the Waldorf Institutes. In this way it attempted to keep abreast of contemporary developments in children’s education and resist parochialism by entering into dialogue with those who shared AMS’s concerns for the educational welfare of children.

AMS succeeded in reviving the Montessori method in the United States and gaining recognition for it as a valid educational system. The society has become the foremost resource in America for Montessori education and teacher training. Through its varied activities it continues to provide information, support, and advice to schools, teachers, and parents, and to integrate the ideas of Maria Montessori and her many followers into the structure of American education. For more information about the current activities of the American Montessori Society, visit the AMS website.