June 1941. Washington, D.C. General G. M. Barnes calls officials form the E. Ingraham Company in Bristol, Connecticut, down to the Capital. The U.S. government needs someone to manufacture an experimental part for anti-aircraft guns, and Barnes taps the Connecticut-based watch and clock maker for the job.

And then “our headaches began,” the company’s president, Dudley Ingraham, wrote several years later.

The company had originally been asked to produce a modest 2,000 parts per day. But then came Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declaration of war. Several months later, the local arsenal accepted the first run of parts on the same day of delivery, and requested the company increase production to 75,000 parts per day.

Dudley Ingraham deemed the new number “fantastic,” though little could be done. The nation had entered World War II and local businesses would now face the demands of total war.

During the war years, the federal government assumed an expansive role in managing the national economy. To help mobilize for war, Washington created new agencies like the War Production Board, the War Manpower Commission, and the Office of Price Administration. These agencies set production quotas, managed the labor supply, and fixed wages and prices. They also pushed industry to retool their factories for the war effort. The experiences of the E. Ingraham Company give just one such example.

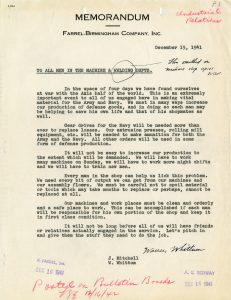

Among the challenges faced by Connecticut businesses, shifting production from the consumer economy to the wartime economy proved most dramatic.

The E. Ingraham Company went from producing clocks and cabinets to making everything from bolts and bullets to filters and radio parts. Similarly, industrial firms like the Farrel-Birmingham Company stopped making tool and dies for civilian purposes and began pumping out gear drives for cargo ships.

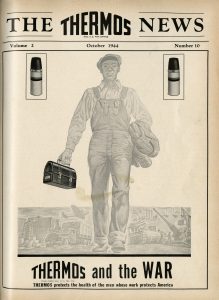

Not every company had to convert their factories for wartime production. The Thermos Company in Norwich simply stuck to making the vacuum-seal bottles they were known for. As the company told its employees, the War Production Board rated Thermos bottles “only two places below the rating assigned to guns, planes, tanks, and ships.” During the war, around 98% of the company’s output went toward military use.

But whether or not they had to retool their factories, Connecticut businesses always had trouble securing materials. The Thermos Company, for example, had to replace aluminum in their bottles first with tin, then steel, and finally paper.

Connecticut utility companies also had to find replacement resources. The Hartford Electric Light Company (HELCO), staring down a dramatic reduction in access to oil, turned to coal for its electric works. The switch forced the company to purchase new machinery and open a new facility. But it released over 5,000,000 gallons of oil to the military.

With the armed forces swallowing up materials left and right, Connecticut businesses sought creative solutions to keep production humming and energy flowing.

Increased production demands and tightening resources also put a strain on day-to-day operations. HELCO, for instance, instituted bi-monthly billing to reduce manpower and mileage on company vehicles. The company also encouraged customers to replace their own fuses and divert repair work to local used-car dealers. Yet they made these adjustments with aplomb. As one service report went: “the organization is alert, trained, and sails have been trimmed.”

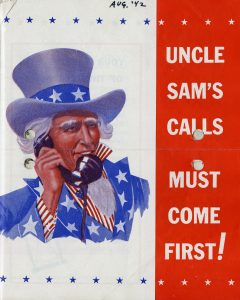

The Southern New England Telephone Company did not show the same level of confidence. In its monthly newsletter, the company constantly warned about stress on the lines and reductions in necessary materials. “New telephones—like new refrigerators and new automobiles—have become a ‘war casualty’,” went one article. Notably, this diminished capacity came from orders of the War Production Board.

Connecticut communications were reduced and redirected to serve the war effort, much to the dismay of local companies and consumers.

Reconverting to civilian manufacture toward the war’s end also posed a problem for some Connecticut businesses. The E. Ingraham Company, which had been forced to retool large parts of its factory, fretted over how to bring civilian production back online. Vital materials like nickel and chromium would remain scarce, and foreign imports would soon flood American markets.

Other firms, like the Thermos Company, had the “enviable” position of producing a civilian product for wartime use. The shift back to the peacetime economy would be more or less seamless.

World War II profoundly impacted Connecticut businesses. As the declaration of war went out, local firms had to quickly adjust. They retooled machines, redirected production toward the war effort, and accepted that the federal government would soon set schedules and fix prices.

While some looked askance at these changes, none refused them. Each company remade itself in the wartime image, and the effects of that transformation went beyond just products and prices. It would touch everything from labor, company culture, and local recognition.