March 1942. Bristol, Connecticut. The latest edition of Union News lands on the factory floor. A shakily-drawn victory “V” sits at the top of the page, surrounded by the slogan: “Everybody’s War – More Action, Less Smugness.”

World War II had arrived in Connecticut industry, and workers were quick to take note.

“Today the vast majority of us are reading the war,” wrote the author of one column, “only few are really living it.” But not for long. “This war will effect [sic] every one of us … None may escape or count the cost.” The piece, titled “War and You,” ended with a familiar refrain, printed in bold: “Don’t forget to pay your union dues.”

The U.S. entrance into World War II radically altered the landscape of American labor. Men and women gave up their civilian jobs in large numbers to serve in the armed forces, leaving local firms scrambling to find replacements.

Publications like Union News, a newsletter produced by workers at the E. Ingraham Company, provide a striking record of these changes. Other Connecticut businesses, such as the New Britain Machine Company and the Thermos Company, covered similar issues in their own publications. Whether in the rough-hewn style of the former or the glossy mockups of the latter, the war’s impact on labor regularly filled the pages of company and employee publications.

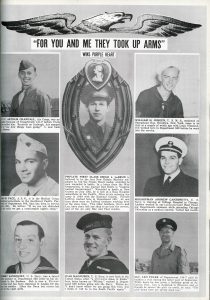

One of the war’s most immediate effects on Connecticut industry was the loss of labor power to military service. By the end of World War II, some 16 million American men had served in the armed forces and around 350,000 women had joined auxiliary units.

This dramatic decline in the civilian labor force meant newly-emptied factories. But workers fighting overseas did not wholly disappear from the workplace. Company publications from the war years routinely paid tribute to former employees. Roll calls, photographs, and testimonies from family and friends connected those at home with absent workers serving overseas.

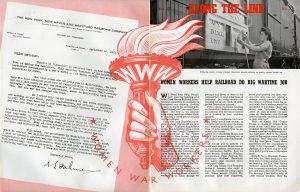

As former employees fanned out across the theatres of war, less familiar faces began to show up in local industry. Although they mostly took service and clerical jobs, a significant number of women found their way into the warehouses and workshops around Connecticut.

Along the Line, a publication produced by the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, printed a letter from company president Howard S. Palmer that described an “invasion” of female workers. They worked in ticket offices and information booths, as they had before the war. But in line with loosening labor rules, women workers could also be seen handling brushes on paint crews, tending fires in the roadhouse, and shaping metal in the blacksmith shop.

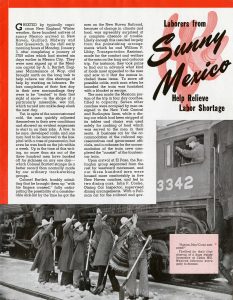

Women were not the only new faces filling jobs around Connecticut during the war. The Bracero Program, a labor agreement first signed by the United States and Mexico in August 1942, brought thousands of Mexican workers over the border on temporary contracts. While usually linked to agricultural work in the southwest, the Bracero program also brought workers to New England.

An article in Along the Line details the roughly 3,000 mile train ride that brought 300 Mexican workers to Connecticut in January 1944 to work on the New Haven line. The workers were let off in towns like New Haven, Guilford, Midway, and East Greenwich, where they were greeted by the cold slush of a New England winter. As in the fields of the southwest, they performed mostly manual labor: laying track, cleaning fires, unloading coal, and shoveling sand.

But even with the influx of new workers, Connecticut firms still fretted over labor shortages. Along with securing new employees, local businesses tried their best not to lose the ones they had.

Company publications routinely ran articles urging workers to guard against workplace accidents and injury. “An injured worker is a wounded soldier,” went the title of one piece. Many articles targeted women specifically, instructing them on the proper clothing and hairstyles needed to safely work with heavy machinery.

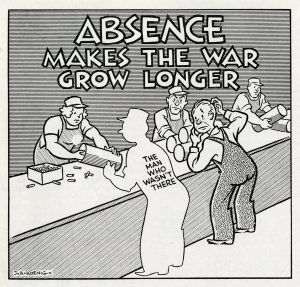

Absent workers also became a threat to guard against. An article in the Thermos News, a publication for Thermos Company employees, made clear that even a single day off the job aided the axis powers.

The wartime changes to Connecticut’s labor force did not last. The civilian employees that left local firms to serve overseas often reclaimed their jobs once they landed back on American shores. Management generally viewed women workers as performing a patriotic service, not assuming an expanded role in the workplace. Mexican workers brought to the United States through the Bracero Program had to return to their home country once their contracts ran out. Yet the demands of wartime production changed the look and feel of Connecticut industry in ways that left a lasting imprint on domestic industry.