September 1942. New Haven, Connecticut. People gather outside a new building at one of the local factories. On a stage facing them sits the speaker’s stand, “bedecked in a blaze of colorful bunting and an enormous blue satin backdrop.”

The “snappy, impressive” Bradley Field Army band occupies the right sight of the stage, drawing “all eyes and attention.” The crowd of mostly workers – over 3,600 of them – stretch back to the wire fence surrounding the property. The day’s events are soon to begin.

The scene was a familiar one for Connecticut businesses during World War II. On that day, the New Britain Machine Company held a ceremony to receive the Army-Navy “E” award. First issued in 1906 by the Navy, “for a job well done,” the Army and Navy began to jointly award the “E” in 1942 to businesses that excelled at supporting the war effort.

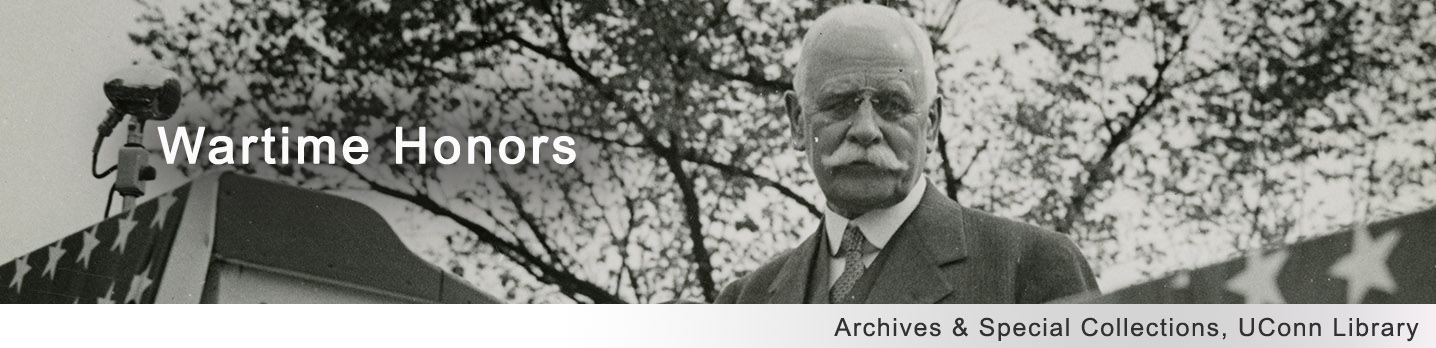

Winning the award always called for a celebration. For Connecticut businesses like the E. Ingraham Company or the American Brass Company, receiving the Army-Navy “E” Award meant hosting stately affairs. Factory workers and their families were invited to eat food, listen to music, and sit through seemingly endless speeches from government officials, local politicians, and company heads.

Although the most coveted, the Army-Navy “E” was only one award given to industry during World War II. Connecticut’s local businesses regularly won acclaim for their production efforts in support of the war.

Sometimes the honors came in the form of an official visit. In July 1943, Brigadier General G. H. Drewery, Chief of the Springfield Ordnance District, appeared at the Thermos Company plant in Norwich, Connecticut. After inspecting the plant, he praised the company’s “sincere efforts” at keeping up the supply of vacuum-sealed bottles for thirsty war workers.

But onsite visits were unusual. Official praise most often arrived by mail. Federal officials applauded Connecticut businesses for their critical efforts to supply war materials, increase production, and adjust to the shortage of workers and raw materials.

Although usually addressed to company heads, these letters often made the rounds on the factory floor. The Hartford Electric Light Company made it a practice to circulate letters among departments and post them on bulletin boards to encourage workers.

Awards for supporting the war effort did not come easy. Connecticut businesses had to supply significant documentation to receive official commendation. Sometimes, they also had to engage in extensive lobbying efforts to win recognition.

After receiving the Army-Navy “E” Award, officials at the Farrel-Birmingham Company faced a problem: the Navy had only labeled its plant in Buffalo, New York, for recognition. The company’s president, Nelson W. Pickering, wrote to correct them.

Failure to recognize their Connecticut plants in Ansonia and Derby, he argued, would have “extremely severe repercussions” for their workers. Pickering’s appeal proved successful, and the Navy changed the award to include all three plants.

The symbolism around the Army-Navy “E” Award was especially sensitive. Managers often had to conduct tedious correspondence with federal officials over questions of which workers would be allowed to wear commemorative pins, which plants could fly the official flag gifted to the plants, and how long the companies could claim the prestige of winning the award.

Indeed, the Army-Navy “E” Award did not last forever. Companies usually could only celebrate the award for six months. Then, they would have to prove again that they had exceeded production quotas.

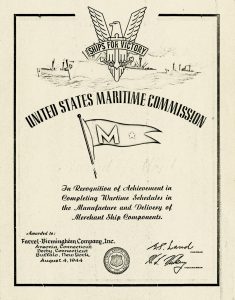

But for those companies that did surpass expectations, each renewed award meant another silver star for the official flag. Some companies, like Farrel-Birmingham, even won awards from other branches, such as the “M” Award from the Merchant Marine.

Ultimately, the honors handed down to Connecticut businesses from the federal government served many purposes. They helped ease tension between federal agencies newly regulating business operations. They spurred workers to meet the high demands of war production. And they supported the government’s overall attempt to boost morale amid the disruptions to work and daily life caused by World War II.