Nancy McCormick Rambusch’s Early Interest in Montessori

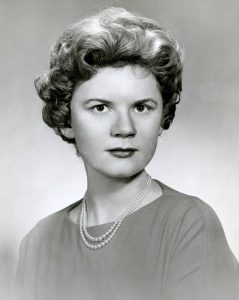

Nancy McCormick Rambusch discovered the writings of Maria Montessori as an undergraduate at the University of Toronto in the late 1940s. Following graduation, she studied in Paris as a French government fellow and had the opportunity to visit a Montessori school. On June 2, 1951, she married Robert Rambusch, and after having her first child the following year, she became more interested in Montessori education as an alternative to the local parochial schools. She attended the tenth International Montessori Congress in Paris, where she met Mario Montessori, the son of Maria Montessori and the leader of the Association Montessori Internationale (AMI). There she learned that she would have to undergo authorized teacher training if she wanted to organize a Montessori school in the United States.

Reintroducing Montessori to the United States

The Montessori method of education was first introduced to the United States in the early 1900s. However, it quickly fell out of favor with American educators. Widespread American interest in Montessori did not return until the 1950s, thanks in large part to Nancy McCormick Rambusch. In September 1953, Rambusch published the first American article on Montessori education written for a general audience to appear in several decades. “Learning Made Easy” was published in the first issue of Jubilee magazine.

In September 1954, pregnant with her second child, and with her son Rob in tow, Rambusch the United States left for London to attend the teacher training course offered by the Maria Montessori Teacher Training Center. She completed the Montessori Primary Course with Distinction in Spring 1955 and then immediately enrolled in the Montessori Elementary Course, which focused on teaching children ages 6-12. Upon her return to her home in Greenwich Village, New York, Rambusch set up a small Montessori playgroup consisting of her own two children and several preschoolers from the neighborhood.

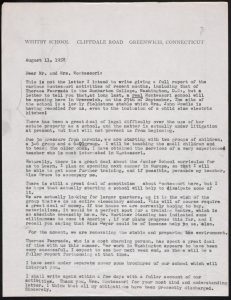

In 1956, Rambusch and her family moved to Connecticut, where she met a small group of parents who were similarly dissatisfied by the education offered by local Catholic parochial schools and who were interested in establishing a Montessori school in the United States. Together, these parents opened the Whitby School in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1958, in a renovated barn on the property of Georgeann Skakel, with 17 students enrolled and Nancy McCormick Rambusch serving as the headmistress. Whitby was the first Montessori school in the United States.

The Growth of Montessori in America

By 1959, the Whitby School had outgrown its original home in the renovated barn and moved into rented classrooms in Byram, Connecticut.

By December 1959, the school had grown to 63 children. In 1961, Whitby moved again—this time into a new 150 student school building in Greenwich, Connecticut. That same year, Time magazine and The Saturday Evening Post published articles on Whitby. These stories helped foster national interest in Whitby and the Montessori method.

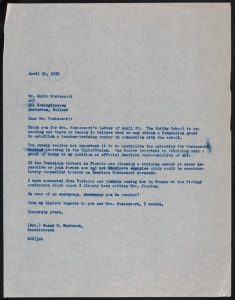

The growing interest in Montessori education in the United States fostered demand for Montessori trained teachers, which were in short supply. While AMI was able to supply some international teachers, Rambusch sought to establish a teacher training center in the United States in connection with Whitby. The first training courses used Whitby classes as a model, giving trainees an opportunity to observe a Montessori classroom in practice.

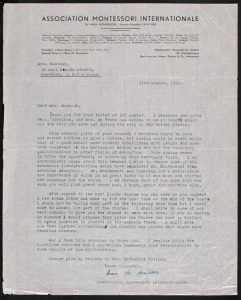

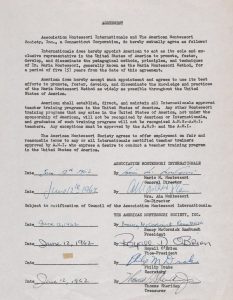

In June 1959, Rambusch was appointed the representative of AMI in the United States. She was tasked with forming Montessori schools in the United States, establishing an institution for training teachers in the Montessori method, and helping to establish a Montessori Society in the United States that would be affiliated with AMI. She founded the American Montessori Society in 1960. Two years later, with Nancy McCormick Rambusch serving as president, the American Montessori Society took over the role of sole representative of AMI in the United States, with the responsibility of promoting, fostering, developing, and disseminating the Montessori method, as well as establishing AMI approved teacher training programs in the United States.

The Americanization of the Montessori Movement

In order for the Montessori method to be taken seriously within the United States, Nancy McCormick Rambusch believed it needed to be integrated into the existing system of American educational training, rather than exist outside of it. Attempts to retain the purity of Montessori teaching by ignoring the latest research in developmental psychology and American educational theory would hinder widespread acceptance of the Montessori method in the United States.

Rambusch was a leading proponent of modifying the Montessori method to fit American culture. While she believed that Montessori education in America should start with the classic model created by Maria Montessori, she sought greater flexibility in the materials used to teach students, the ages at which students were supposed to master certain skills, and the role of Catholicism in Montessori education. Although Rambusch was active in Catholic circles, she recognized that Montessori had to transcend religious boundaries and would have to acquire nonsectarian appeal if it was to succeed in the United States. She also firmly believed that aspects of the Montessori method had to be modified to accommodate the culture of mid-twentieth century America and its children, and that the movement should not be confined to private institutions.

These ideas strained relations with AMI, which felt that Dr. Montessori’s principles were universal and could not be modified without destroying their integrity. Despite good-faith attempts on both sides, the philosophical differences could not be reconciled, while additional controversies over finances and control deepened the rift. Ultimately, in 1963, AMI withdrew its recognition of AMS as a Montessori society, and from that point to the present AMS has existed independently of AMI.

In “A Long Letter to Montessorians in America,” (1963) Mario Montessori looked back on the origins of the American Montessori movement. Despite their differences, he spoke of Rambusch with admiration as “[t]he young woman who, unknown in the educational field, alone, unqualified and unexperienced set herself to struggle against the might of organized prejudice in order to achieve the re-introduction of Montessori in America.” He credited her with the revival of the Montessori movement in the United States:

“It was Mrs. Rambusch who illustrated [the results of the Montessori method] in articles and in lectures, and when people came and saw for themselves, Montessori ‘exploded’ in the United States, and with it exploded Mrs. Rambusch by multiplying her efforts to propagandize Montessori all over the country. . . . I wonder how many nights she slept, or how many of them at home. I wonder how in all this turmoil she found the time to write a book or to cope with the confusion of people who insisted in starting schools and Montessori groups and importing trained or half-trained people from Europe and Asia.”

The American Montessori Society experienced challenges common to many new organizations. It was bombarded with a growing national interest. Demand for information about the Montessori method, advice on how to start Montessori schools, and requests for Montessori-trained teachers quickly overwhelmed the society’s limited resources. In an effort to improve the functionality of the organization, the AMS Board hired Cleo Monson as Executive Secretary in January 1963. In June of that year, Nancy McCormick Rambusch resigned as president of AMS and embarked on a distinguished career in children’s education. She continued to be a prominent voice in the American Montessori movement until her death in 1994.